by James Wright

I have spent the last six months writing a book. Quite a long book too. One that I’m very proud of. It’s not a dry or dusty textbook. Instead, my book is the narrative of people living their real lives – full of hopes, fears and desires – across over one thousand years of history.

I have spent the last six months writing a book. Quite a long book too. One that I’m very proud of. It’s not a dry or dusty textbook. Instead, my book is the narrative of people living their real lives – full of hopes, fears and desires – across over one thousand years of history.

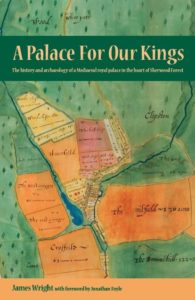

The book, A Palace For Our Kings, tells the story of one of the largest Mediaeval royal palaces ever to have graced the British Isles. One that stood right in the heart of ancient Sherwood Forest, the landscape of legends, near a village called Kings Clipstone. It is as much the story of ordinary people – farmers, clerks, huntsmen and builders – as it is of kings, dukes, bishops and knights.

These six months have been based on over twelve years of research and fieldwork which themselves stand on several hundred years of study. They have undoubtedly been bolstered, encouraged and supported by a wide-ranging group of communities without which I could not have succeeded. Yet until very recently this was a site that had gone largely unnoticed.

There are fleeting references to Kings Clipstone in other books written on Mediaeval buildings and the occasional mention in biographies. Most authors assumed that it was nothing more than a minor residence, treated it as such and moved on without further comment. Many local people still see the roofless, ruined walls and consider it to be nothing more than an insignificant hunting lodge.

I first visited King John’s Palace on a very cold and blustery day in February 2004. I knew that these were the remains of a Mediaeval building that had associations with eight of the Plantagenet kings. Over time I began to understand that it was all that remained of a mid-twelfth century great hall built, in the French style, for Henry II. Once it did not stand alone on its hill in splendid isolation, but was part of a sprawling complex of buildings that covered over seven and a half acres of ground. This was once a vast palace, yet for centuries it had lain dormant and under-appreciated.

I was frightened by what I saw. The stonework was in a terrible state of repair, very close to collapse. What gave me confidence and direction was the tremendous vision, passion and enthusiasm of the landowners. They see themselves as the custodians of the site and their self-appointed duty is to pass on King John’s Palace to future generations intact. Five years later we were able to make good that promise through a generous programme of funding by English Heritage. That funding was hard won and was based on a great deal of research and campaigning.

Much of the recent story of the site has felt like a constant drive to reassert its internationally significant heritage. There was a real need to prove the importance and scale of the palace at Kings Clipstone. Whilst the prevailing notion remained that the site was just a ruined hunting lodge there was little chance to attract attention. The work has involved a multidisciplinary approach involving field and buildings archaeology, remote sensing, map regression, art and architectural history, landscape survey, documentary history, travelogues, historiography, nature conservation, oral history, etymology and consultation of a wide-ranging amount of secondary sources.

Gradually the true history of the palace re-emerged. It was visited by eight kings who held parliament, Christmas feasts and tournaments; were visited by the king of Scotland, a papal envoy and traitorous barons; built a fortification, great hall and a stable for two hundred horses; went hunting, drank wine and conceived a prince; listened to storytellers, poets and singers. Only when this story arose did Kings Clipstone have the chance to be taken seriously as a site that had a major significance.

Much of what I have worked on, in particular during the last six years, has been completely unfunded and voluntary. That’s just how it is in the heritage sector. Without a consistent programme of funding from the public or university sectors the majority of research is carried out according to the specific legal requirements needed as part of development or conservation.

Work at King John’s Palace has therefore bumped along on occasional pots of money, but has effectively been brought about by community volunteers. Of which I am just one. There have been several occasions when I thought that I had done my last piece of work on the site and could not clearly see a future for my involvement. However it has always been that local community determination which has unblocked the road and enabled me to persevere. Without this support there would not have been a book. I am very grateful and honoured to have worked with such supportive and visionary people.

And that is ultimately what it has always been about. The people of the palace. Past, present and future…

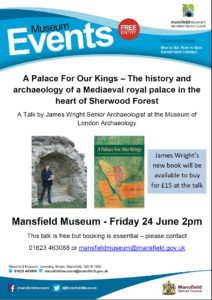

James Wright is a Senior Archaeologist at the Museum of London Archaeology. His book ‘A Palace For Our Kings – The history and archaeology of a Mediaeval royal palace in the heart of Sherwood Forest’ will be published during the summer of 2016.

This blog article was originally published via the History & Archaeology of Kings Clipstone Facebook page.

The tremendous success of our first title – A Palace For Our Kings by James Wright – has led to great demand for a second print run. The book sold out of its entire first edition in under three months.

The tremendous success of our first title – A Palace For Our Kings by James Wright – has led to great demand for a second print run. The book sold out of its entire first edition in under three months.

As well as being available from online suppliers,

As well as being available from online suppliers,  Renowned architectural historian Dr Jonathan Foyle has contributed the foreword to A Palace For Our Kings by James Wright. The book relates the history and archaeology of a Mediaeval royal palace in the heart of Sherwood Forest.

Renowned architectural historian Dr Jonathan Foyle has contributed the foreword to A Palace For Our Kings by James Wright. The book relates the history and archaeology of a Mediaeval royal palace in the heart of Sherwood Forest.

I have spent the last six months writing a book. Quite a long book too. One that I’m very proud of. It’s not a dry or dusty textbook. Instead, my book is the narrative of people living their real lives – full of hopes, fears and desires – across over one thousand years of history.

I have spent the last six months writing a book. Quite a long book too. One that I’m very proud of. It’s not a dry or dusty textbook. Instead, my book is the narrative of people living their real lives – full of hopes, fears and desires – across over one thousand years of history.